This is the government page of the Kanyen’keha:ka or Mohawk people of the Six Nations. Kanyen’keha:ka people live in two main territories: Six Nations of the Grand River and Kanyenke or the Mohawk Tract, also known as Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory.

General inquiries about this website may be sent to info@kanyenkehaka.com.

Keepers of the Eastern Door

The Mohawks are Onkwehon:we – original, or “real” people – who belong to the “Iroquoian” language group in the area surrounding Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence river. In our own language we call ourselves Kanyen’keha:ka “the people of the flint or crystal” (the crystal being a reference to the “Herkiemer diamonds” found in the Mohawk valley.)

Renowned as fierce and uncompromising warriors, Mohawk people have long played a central role in the political fortunes of Turtle Island.

Our main villages were located on the Tenonanatche (meaning a river flowing through a mountain) or Mohawk River, which was one of the few passages through the Appalachian mountains. The river flows from Lake Oneida down to the Hudson river, and from there out to New York city and the Atlantic.

The Mohawks and the others of the five lands were spread out along this river system, and through it controlled the main east-west corridor through the Appallachian mountains. Because of our geographical location and the flow of the waters, Mohawk warriors could descend upon our enemies quickly from practically any direction.

One reason that we Mohawks have had such significant influence is because we were the first nation to accept the Kayenere:kowa or Great Peace, and thus became both the “elder brothers” of the powerful Wisk Niyohontsyake (Confederacy of the Five Lands), and the keepers of its “Eastern Door.” This meant that within the Confederacy, the Mohawks had the responsibilty for dealing with the European nations who were arriving across the oceans to the East.

Being the “older brothers” within this confederacy gave the Mohawks great powers and responsibilities as according to the Kayenere:kowa they and the Seneca are the “well” into which all potential agenda items were put. No Confederacy business could be brought forward without the agreement and active support of the Mohawks.

The confederacy of the Wisk Niyohontsyake (also known as the Haudenosaunee) not only included the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca nations, but also several dozen other nations that came under its protection including the Deleware, Nanticoke, and Tutelo nations.

The Wisk Niyohontsyake arose before European contact in the context of widespread warlordism and blood feuds. The creation of the confederacy was a tremendous organizing achievement that saw 49 matrilineal clan families from five different Iroquoian lands unite together under a common set of guidelines and procedures designed to promote universal peace and harmony.

According to historian Ray Fadden, at its peak, the Kayenere:kowa goverened a landmass larger than that held by the Roman Empire.

Arrival of the Easterners

In 1534, a French military exploration mission led by Jacques Cartier sailed up the St. Lawrence – entering deep within Iroquois territory. Cartier claimed the territory as a possession of King Francis I, but described a territory filled with Indigenous inhabitants. On the site of what is now present day Montreal, Cartier visited an Iroquoian village called Hochelaga – a palisaded village containing over 50 longhouses.

Cartier erected crosses on high points of land, kidnapped local Onkwehon:we youth to bring back to Europe as translators, and otherwise antagonized the locals. Cartier established the French’s first permanent settlement “Charlesbourg-Royal,” in 1541, but the French were driven out of the territory they claimed the following year. They did not come back to Turtle Island for 60 years, when Samuel de Champlain returned in 1608 and established permanent settlements in Port Royal and Stadacona (Quebec City).

When the French returned, they noted that many of the thriving Indigenous villages they had earlier visited were gone, and the population greatly reduced. A similar phenomenon was noted along the east coast by English explorers. Lands that were once covered with people and villages were now empty and the forests were overgrown. This is most likely a result of diseases spread by the Europeans and by the Indigenous “translators” they kidnapped, brought back to Europe, and who later escaped to their home communities.

When Champlain returned to lead a new effort of French colonization, he immediately rekindled French hostility to the Iroquois, and in 1609 he personally led a French-Algonquin war party against the Mohawks near Fort Ticonderoga. Champlain’s arquebus fire killed numerous Mohawk warriors including three chiefs and inaugurated a century of warfare between the French and the Mohawk/Iroquois.

Taught a deadly lesson on the effect of firearms in battle, the Mohawks began to trade with the Dutch and the British to acquire their own weapons. The Dutch led by Henry Hudson began exploring the Hudson river in 1609, and established a colony on the Island of Manhattan in 1624. The Dutch made peace and friendship agreements with the Mohawks and the Haudenosaunee confederacy.

The 17th century was a period of intense rivalry between the Dutch, French and British, over who would ultimately colonize the North-East of Turtle Island. The 1640s were known as the Beaver Wars, as the European hunger for furs drove various Indigenous nations into battle for control of hunting grounds and trade routes.

The Dutch firearm trade with the Mohawks provided a counter balance to French aggression, but the Dutch surrendered “New Amsterdam” – what is now New York State – to the British in 1664.

One the key reasons for French success in penetrating deeper into the continent then any other European nation was through the efforts of the Jesuit missionaries who carried out diplomatic and spying missions.

In 1666 the French intensified their attacks on the Iroquois through direct invasion of the Mohawk Valley. In 1666, 500 French soldiers along with their Indigenous allies were led by Daniel de Rémy de Courcelle, and invaded the Iroquois homeland in present-day New York.

In 1667 a second French invasion of 1300 led by Alexandre de Prouville, the “Marquis de Tracy” and Viceroy of New France, was successful in a “scorched earth” attack on Mohawk villages and crops. The Mohawk were forced to sue for peace, and it is at this time that a section of the Mohawk Nation, along with some Onondagas and Senecas broke off to join the French orbit.

This group settled in what became Kahnawake, Akwesasne and Kanehsatake under the watchful eye of the Jesuits and Sulpician religious orders and acted as military allies of the French. In leaving the mainstream of the Mohawk Nation and accepting French protection and Catholic religious instruction, these Mohawks left behind their titles and political connections to the people of the five lands.

However, the Eastern Mohawks did not abandon their concepts of political organization, and they built new council fires and confederacies informed by the Kayenere:kowa. They formed the Tsiata Nihononwenstiake, or the Confederacy of the “Seven Lands.” The Confederacy was composed of the Onondaga of Oswegatchie, the Mohawk of Akwesasne, the Mohawk of Kahnawake the Mohawk and Anishinaabeg (Algonquin and Nipissing) of Kanesatake, the Abenaki of Odanak, the Abenaki of Bécancour (now Wôlinak), and the Huron of Jeune-Lorette (now Wendake).

While Mohawks often tried to avoid killing each other on the battlefield, this split in the Mohawk nation was to have lasting consequences that continue to this day.

The Mohawk-British silver covenant chain relationship

Once the British displaced the Dutch from the Hudson river and what is now New York, the Mohawk nation established a close alliance with the British Crown. In 1710 “Four Mohawk Kings” visited the court of Queen Anne in England, and the “Silver Covenant Chain” of Mohawk–British alliance is usually dated to this interaction.

The key link in this relationship was Sir William Johnson, the nephew of a Scottish lord who established himself on the Mohawk river in 1738. He brought families of highland Scots, including their clan chiefs who settled on the Mohawk River and were loyal to the Crown. Johnson and his men became close friends and trading partners with the Mohawks. Johnson was appointed the Crown’s first Indian Agent, became the husband of Mohawk clan mother Molly Brant. The Mohawk relationship with the British was vital to the Crown’s continued existence on the continent.

The Mohawks led the British to a final military victory over the French in 1759, saved the British Colony from a generalized Indian war during “King Pontiac’s Rebellion” in 1763 (and before that during King Philip’s 1675-76 war), defended the British Crown in the American Revolution, halted the American invasion of Canada in 1812-14, and mobilized to defend the Crown in the rebellion of 1837.

In other words, without the Crown’s relationship with the Mohawk Nation, the Crown would never have secured or maintained its claim to any of the lands now known as Canada.

When the American rebellion against the British Crown began in the 1770s the Mohawks took the British side. The rebellion occurred in significant part because the Royal Proclamation of 1763 stopped unscrupulous colonials from purchasing Indian land and required a “legitimate” surrender of that land to the British Crown. Other nations within the confederacy sought to remain neutral, and some like the Oneida, actively supported the Americans and warred against the Mohawks.

Despite the heroic efforts of Mohawk warriors led by warriors such as Joseph Brant, John Norton, John Deserento, Isaac Hill and many others, all the Mohawk villages and settlements in the Mohawk valley destroyed in a scorched earth campaign carried out by General Sullivan at George Washington’s orders.

The Mohawks and such others of the Six Nations that followed them resettled along the banks of the Grand River and at the Bay of Quinte, the birthplace of Tekanawí:ta the peacemaker who created the Kayenere:kowa.

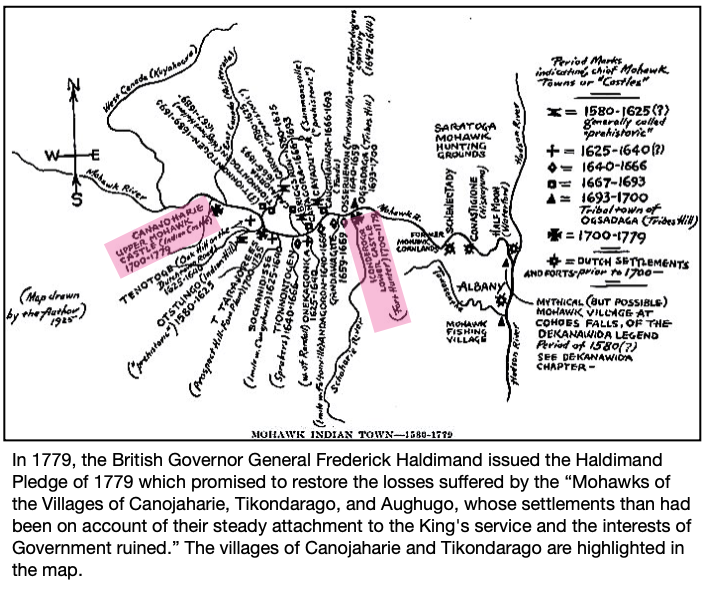

In 1779, Sir Frederick Haldmand issued the Haldimand Pledge of 1779 which promised to restore the losses suffered by the “Mohawks of the Villages of Canojaharie, Tikondarago, and Aughugo, whose settlements than had been on account of their steady attachment to the King’s service and the interests of Government ruined” … “the same should be restored at the expense of the Government, to the state they were in before the wars broke out, and said promise appearing to me just, I do hereby ratify the same.”

In 1783 the Treaty of Paris established peace between the British and Americans, but did so without any consultation with or mention of the Iroquois whose land this war had been fought on.

The lands on the Bay of Quinte were set aside as lands for the whole of the Six Nations under the Simcoe Deed of 1793, but were predominantly occupied by the Mohawks. Mohawks moved to both Six Nation and Bay of Quinte in 1784. The Mohawks with Brant travelled from Niagara, the Mohawks with Captain John Deseronto come from a community they built in Lachine, across the river from Kahnawake in Montreal.

The settlements along the Grand River followed the traditional system, with each nation setting up in their own villages along the Grand River. The Mohawks were based in Brantford, the Onondaga in the village of Onondaga, the Tuscarora in what is now Ohsweken, the Cayuga in the present day town of Cayuga, the Oneida near what is now Caledonia, etc. About half of the original population on the Grand River were Mohawks, while the rest came from another dozen or so Indigenous nations.

The Haldimand Promise and the Haldimand Proclamation confirmed that the Grand River lands were to be reserved for the Mohawks in compensation for the losses of their homes in the Mohawk valley. The other nations of the Confederacy still retained their territory and were not expelled from their lands, though Brant tried to attract as many Indigenous people from as many lands as possible to the Grand River tract. Brant sought to build an independent Indigenous territory on the Grand River by taking advantage of the new technologies and social order brought by the British. He encouraged agriculture and like many Grand River Mohawks became an Anglican and a part of the official British church.

The Mohawks in Tyendinaga were predominantly from the Fort Hunter village in the Mohawk valley and were critical of what they saw as Brant’s closeness to the British. However the Mohawk members of these two communities are closely related, and indeed are the same people.

Canada’s Confederation and the Indian Act

After the American revolution, an alliance of United Empire Loyalists and allied Indigenous nations preserved the Crown’s presence in what is now Canada, and it was not until the mass migration of the 1840s and the push towards Canadian Confederation, that the Crown abdicated its responsibilities to its Indian allies to a self-interested Canadian colonial elite.

In the 1840s as new waves of European immigration flooded into upper Canada, a systemic effort was undertaken to take land away from the Mohawks. By 1844 fraudulent land surrenders had reduced the Haldimand Tract to the size of the current reserve as Six Nations (less than 5% of the original land) and the lands of the Simcoe Deed were fraudulently surrendered.

The Confederation of Canada in 1867 for the purposes of railroad building and raw material extraction inaugurated the “dark days” faced by the Mohawks and many other Indigenous nations. The Indian Act was created in 1876 and was intended to solve Canada’s “Indian Problem” by assimilating and destroying the Indian population through religious indoctrination, boarding schools, and the reservation system. The Mohawks were one of the nations to resist the Indian Act the longest, but in 1924 under the leadership of Duncan Campbell Scott, Canada imposed the Indian Act system and a Quisling “elected Band Council” in Mohawk communities through military force.

The RCMP literally invaded Mohawk territory, arresting leaders and confiscating all instruments of governance – files, money, wampum belts, etc. – and then built a barracks right in the centre of Ohsweken for their troops to enforce the new political system. Clan Mothers and Chiefs were rounded up and thrown into Kingston penitentiary.

Ever since this time, Elected Band Councils have ruled over Mohawks, despite the continued refusal of Onkwehon:we people to participate in the political system of the “ship” through elections. Many have preferred instead to keep their own culture and politics alive in the world of the “canoe.” Over this time of enforcement of the Indian Act through military occupation, the Mohawks and other members of the Confederacy continued to resist Canadian colonialism and to meet in accordance with their traditional ways.

Despite the mistreatment of its allies, the Crown continues to commemorate its Silver Covenant Chain with the Mohawks. On its 300 year anniversary on July 4 of 2010, Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip arrived in person to Toronto to make a gift of silver church bells in honor of that relationship to the Royal Chapels in Tyendinaga and Six Nations.

This resistance of the Mohawks has had a global impact, as the Mohawks are renowned across the world for their struggle against the Quebec Provincial Police and the Canadian Army during the Oka Crisis of 1990. The Mohawk Warriors society has been at the forefront of the most militant and effective land defenses since then, most notably at Six Nations in 2006 and Tyendinaga in 2008 and 2020. The Mohawk “Warrior Flag” or “Unity flag” has become ubiquitous in the struggles of the peoples of Indigenous nations around the globe.